[ad_1]

A tiny art gallery on the moon; an artists’ residency at the foot of Mount Everest; an all-access warehouse museum in the Netherlands: A space for art can be many things, once the white cube is broken down.

The effort must be to surprise, inspire awe, offer a one-of-a-kind experience, says museologist Vinod Daniel. After all, today’s art and heritage spaces are also competing with the digital world, the online scroll, amusement parks and Netflix.

“Dubai’s Museum of the Future offers a sense of make-believe and future possibilities, which appeals to a demographic that museums miss out on: the young. It’s a massive blockbuster show,” says Prateek Raja, founder of the contemporary art gallery Experimenter in Kolkata. “We’re at that point where the objective is to bring more public accessibility to exhibitions.”

It’s interesting to think that museums themselves were a revolutionary pivot towards democratisation, when they first opened. Until the inauguration of the Louvre in Paris in 1793, for instance, the most magnificent collections of art and artefacts were private, belonging to the Church, royalty and aristocracy.

Now, in Paris, things are coming full circle, with a 250-year-old former bourse building being used to house the massive collection of a single man, the French billionaire François Pinault. He’s opening it up to the public, complete with a restaurant run by Michelin-starred chefs. And that’s just the least surprising way in which museums and art spaces are changing.

There is now a gallery on the International Space Station, a prototype for one on the moon by 2025; an artists’ residency and exhibition space near Nepal’s Everest Base Camp; and Rotterdam’s Boijmans Van Beuningen reopened as a depot / museum in November, where visitors can access its entire collection of over 1.5 lakh pieces and interact with restorers, carers and curators.

Even in India, things are changing in surprising ways. A new museum in Kerala lets visitors “talk” to a late chief minister’s hologram; last year, Kolkata’s Experimenter gallery took an exhibit on the Sundarbans to the Sundarbans, where it still stands.

“It’s all a question of how museums are responding to the present climate,” says art critic and cultural theorist Ranjit Hoskote. “In terms of technology and in terms of a much more diverse public than ever before.”

We’ve been here before

Among the catalysing factors driving the change, two stand out: evolving technology, and the pandemic.

“No serious museum at any time after, let’s say, the end of World War 2, has taken its audience for granted,” Hoskote says. “That is when complex, turbulent shifts of world view, generational attitude, and collection practice came into play. Today these shifts seem exaggerated in magnitude because of the huge technological shifts we’re experiencing and the general precarity of life.”

After the shutdowns of the pandemic, spaces are reaching out with greater urgency. They’re asking, how can we engage individuals with varying levels of cultural capital, Hoskote says. How can we make our collections seem more available? How can we make the interaction seem more two-way?

This kind of move also has precedent. It caused ripples when London’s Victoria and Albert museum first opened its restaurants and souvenir stores, inviting people to sit, chat and buy things. Henry Cole, founding director of the V&A, got the idea for a museum restaurant (tea and a bun or a hot meal) while managing the Great Exhibition in 1851. The museum opened in 1852; its refreshment room in 1856.

“Concepts changed as early as the Industrial Revolution, with its world’s expos that showcased new technologies, arts and crafts, and opened up the idea of the museum, in the form of an exhibition, as something everyone regardless of differences in social standing or class could engage with,” says Rajeev Thakker, architect and artist and former curator of Studio X Mumbai, a space for experimental art, design and research.

The flip side

There are risks, Hoskote warns. “The whole point of the museum is to function as a forum where you think through, with greater depth and intensity, major questions of identity, belonging, inclusiveness, and these are key questions for every society today,” he adds. “You don’t necessarily need the museum to amuse people with light-weight displays of technological novelty.”

The role of galleries and museums, art and history, is to invite the viewer in, but also challenge them. It’s the question of how you use technology, Daniel agrees. And the way to use it best is to first get the message right.

The early 21st century saw diversity play a pivotal role in the shifts of museum practice at the time, for instance. In Europe, there was a strong awareness of the large immigrant populations and questions raised about how to make a collection of Baroque paintings relevant to people of Turkish or Ukrainian origin; of how to build bridges between evolving communities and long-standing institutions.

Who is it for?

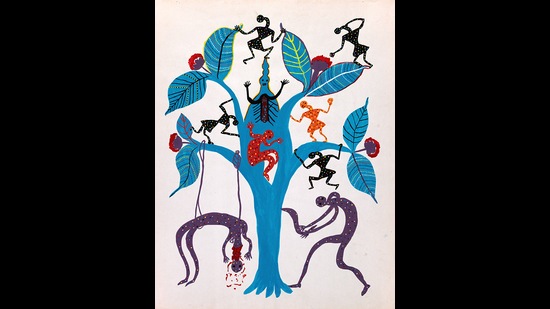

The question: Who is it for, immediately alters how one views an exhibit, says Prateek Raja of Experimenter. “The venues that you choose become a starting point for a conversation and it could make the museum or art gallery visible.” In 2021, Experimenter hosted a project on the Marichjhapi massacre of 1979, the forcible eviction of Bengali lower-caste refugees from the Marichjhapi island in the Sundarbans and the deaths of thousands by police gunfire, starvation and disease.

After asking, ‘Who was it for’, the gallery moved the project to Kumirmari, an island across from Marichjhapi, as a series of enlarged images. The outdoor exhibition will stand until it falls apart or is destroyed by one of the region’s too-frequent cyclones. Art is also about what discussions it brings about, Raja says.

After the Bolshevik Revolution, art and grand fittings from the palaces were installed at railway stations in Moscow / St Petersburg, turning them into grand statements and a kind of museum too, says Naman Ahuja, art historian, curator and Professor of Indian Art and Architecture at Jawaharlal Nehru University. “That kind of public access to art and culture was something the world had not seen before. Nearly 100 years later, the city of Mumbai created T2, and art was put in an airport terminal on a massive scale turning the entire experience of being at the airport into one where travellers can engage with elements of culture and heritage.”

Where to next?

The art of the future could be a collaboration between humans and AI. It could be graffiti on a college campus. It could be both. Digital platforms will remain a key repository and gateway.

Already, they are changing how we look back, and what we look at when we do. Click hereto read about the digital Encyclopedia of Indian Art created by art collector Abhishek Poddar and curator Nathaniel Gaskell, featuring treasures going back 10,000 years, as well as conversations and features on artisans and traditional arts and crafts communities.

In the future, there must be more intersectionality, says Parmesh Shahani, former director of the Godrej India Culture Lab and author of Queeristan: LGBTQ Inclusion in the Indian Workplace. “There are so many people that existing museums have ignored over the years, not just as audience members but also in terms of containing or representing our stories,” says Shahani. “These include people who might belong to LGBTQIA, Adivasi, Bahujan, Dalit or other historically ignored communities; people from regions of our country like the Northeast, who are often left out of mainstream imaginations; people who are differently abled, and so on. For museums to become relevant to the future, they need to place these multiple intersecting communities, and our experiences, front and centre. Because these audiences are growing, and we will either go elsewhere or create our own alternatives.”

.

TAKE A TOUR: FOUR MUSEUMS STEPPING INTO THE FUTURE TODAY

An art depot thrown open

It was a storage crisis that prompted the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam to hit reset. Its five storage spaces spread across the Netherlands and Belgium were old, even flooding and leaking at times. If they were going to build a dedicated depot space, the museum decided, why not also find a way to throw it open to the public?

And so, in 2017 ground was broken on the new facility, and in November 2021 the Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen opened next door, its entire collection of 1.51 lakh art works on display within its new storage vaults.

While museum depots have been opened to the public in the past, Depot Boijmans is the world’s first art institute to make its entire collection accessible to visitors. This includes 63,000 paintings, photographs, films and objects, and 88,000 prints and drawings, including works by the Spanish surrealist master Salvador Dali and British-Mexican surrealist Leonora Carrington.

The works themselves are mounted on movable frames, just as they would be in storage. Guided tours allow visitors, wearing special dust coats, to enter depot compartments for limited periods. Guides offer information on the art works and the facility. To protect the works, a 90-minute gap is maintained between groups, to allow the climate to re-stabilise. The new space also lets visitors interact with experts as they work on aspects such as art preservation.

Because the art works are organised by size and climate zone (rather than genre, era or artist), visitors must necessarily browse, discover new names, make new connections. The idea being similar to that of a library, where one comes in looking for one book, but often leaves with a few others too.

There are screening booths where visitors can access a digitised film library and gallery space for small exhibitions. The depot also has a restaurant and a rooftop garden.

The seven-storey structure, built by local architectural firm MVRDV, is interesting in itself. It is a smooth, tapering ovoid shape made up of mirrored glass that reflects its surroundings, making the structure itself almost disappear.

Art and the museum need to be sites for dialogue, says Yoeri Meessen, head of education at the depot. “Access, like dialogue, is not a one-way street. The public depot enables the Boijmans museum to be more participatory and more transparent. The purpose is to democratise the cultural institution and make it accessible to a diversity of audiences, parallel to the social transitions of our times.”

As for the museum, it is set to reopen in 2029 and function as it always has. “This will be a very exciting new dynamic,” says Jeroen van der Hilst, press officer at the museum and depot. “In one building will be precise and insightful exhibitions; in the other, visitors can see all the goings-on behind the scenes.”

.

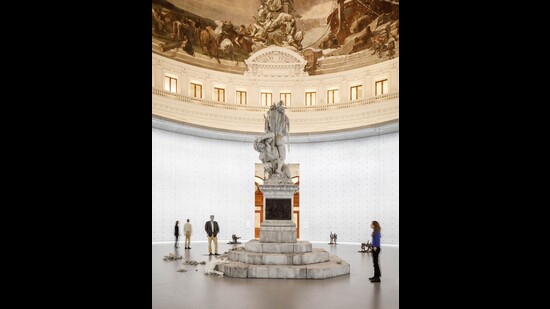

At a former grain exchange

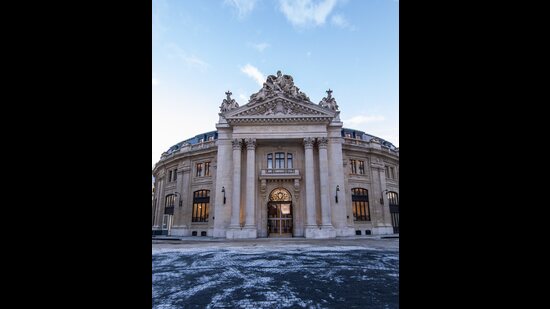

In a museum that is a clear reflection of its times, a former commodities exchange near the Louvre in Paris has been repurposed to house a massive collection of 10,000 works, all belonging to a single French billionaire.

François Pinault, founder of the luxury group Kering and the investment company Artémis, has acquired the Bourse de Commerce on a 50-year lease. This is a neo-classical heritage structure that was built as a grain exchange in 1763 and turned into a commodities exchange, or Bourse de Commerce, in 1889. It was reopened in May 2021, as Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection, following a three-year restoration by Japanese architect Tadao Ando.

The building will eventually house a collection that ranges from a Picasso and a Piet Mondrian to sculptures and installations by 400 contemporary artists, including Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, Urs Fischer and Cindy Sherman.

The first exhibition at the museum, Ouverture (French for Opening), which ran until December 31, sought to represent fresh perspectives on art amid the idea that art should be more accessible to the public, as it is in Italian churches and public squares. One of the centerpieces was a 6-metre-high wax replica of the 16th-century marble sculpture The Abduction of the Sabine Women by Giambologna, which stands at the Piazza della Signoria in Florence.

When the exhibition opened, the replica was perfect, precise, hyper-realistic. Then a wick was lit and it slowly melted.

To continue the conversation between old and new, the museum’s restaurant, La Halle aux Grains, is centered on grains, beans and cereals, in a tip of the hat to the building’s history. It is run by Michelin-starred father-son duo Michel and Sébastien Bras.

The museum is open to the public six days a week, at €14 (about ₹1,100) per head.

A ticket to the moon

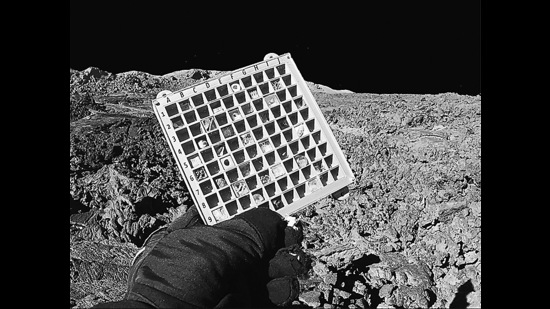

What might art look like in an inter-planetary future? The Moon Gallery aims to explore that question. The plan is to install it on the Moon by 2025, as mankind’s first permanent extraterrestrial exhibition.

A prototype, also called the Moon Gallery, is currently housed at the International Space Station. It will orbit Earth until December, when it will return here. It consists of 64 tiny art works and one engraved AR work, each no larger than 1 cubic cm (1 cm x 1 cm x 1 cm). The eventual gallery will hold 100 such artworks, installed on a segmented metal tray, riveted to the exterior of a lunar lander.

A seed, a shell, ideas of home… each of the works in the prototype represents how perceptions change once an idea leaves its home planet. American artist Minna Philips’s work, Memory, is a tiny cement cube with a hole cut into it in the shape of a cone, evocative of a piddock’s shell. It’s an absence that still speaks of presence, long after the piddock is gone.

The Seed is simply a preserved seed that had begun to sprout. On Earth, this is unremarkable; but as the first seed sprouting on the moon, it would represent a minor miracle and aims to encourage people to reexamine the idea of the seed from the perspective of a child.

The Moon Gallery is an initiative of the Moon Gallery Foundation, a non-profit cultural organisation launched in the Netherlands to promote interdisciplinary and international cooperation in an inter-planetary future.

What could it do for how art itself is viewed? The white cube has become so synonymous with the idea of a gallery that even when one discusses a gallery on the moon, “people think we are literally somehow building a structure with paintings to hang on its walls,” says Elizaveta Glukhova, co-curator of the gallery and co-founder of the Foundation. “Placing art in an alien environment will allow us to rediscover things about art and creativity.”

Because there’s another really important aspect to space faring, and that is the survival of cultures, adds co-founder and co-curator Anna Sitnikova. “We are all hoping the species will begin to move somewhere, but what is all the moving about, in an emotional sense? That is what we are exploring.”

The fact that it’s also “almost silly… actually sending exhibits to the moon, makes it a very nice entry point to the conversation,” says Moon Gallery communications manager Lejla Sarcevic. “To me the democratisation of art is people thinking about the gallery as absurd, but fun and neat, but also then moving on to think about what’s in it, the material science of it, ideas of pop art or fine art. And suddenly people who weren’t really thinking about art at all, are thinking about it from a different perspective.”

A new challenge at Everest

The Denali Schmidt art space sits at 3,775 metres, about 30 km from Nepal’s Everest Base Camp. As the snows around it melt amid the climate crisis, it makes a statement on sustainability.

The space is offering artists from around the world a chance to visit and work , and turn some of the tonnes of waste left behind by climbers each season into art. The first artist on site, Lukas Zeilinger from Germany, arrived this April and created an installation inspired by the Tibetan prayer flags strung up in the mountains.

Starting May 13, American painter Emma Fern Curtis of the Denali Foundation (set up in memory of the mountaineer Denali Schmidt who died while attempting K2) will spend five weeks here, conducting art workshops with locals.

The residency space sits adjacent to the Sagarmatha Next Centre of upcycled art. Both are part of a larger project led by the non-profit organisation Himalayan Museum and Sustainable Park, with the residency also supported by Denali Foundation.

“Our mission is to create a sustainable waste-free zone in the Khumbu / Everest Region in the high mountains of Nepal,” says project director Tommy Gustafsson.

In the distance, Mount Everest soars about 30,000 feet above sea level, a pristine white that belies the trail of garbage mountaineers leave in their wake. During a 45-day cleanup project in 2019, the Nepalese government collected nearly 11 tonnes of debris, including plastic bottles, cans, food wrappers, equipment, batteries, and human faeces, from the sides of the mountain.

“The visiting artists will also conduct workshops for visitors as well as local children and adults,” Gustafsson says. “Right from the start we want to establish that this gallery is for everyone; for the people living in this high-altitude region, for visitors, and for the artists that we hope to bring in from different communities, countries and cultures.”

Enjoy unlimited digital access with HT Premium

Subscribe Now to continue reading

[ad_2]

Source link

E2 inducing increase in the proliferative potential of T47D cells was also demonstrated by growth curve, while fulvestrant completely reversed such growth promoting effect buy cialis with paypal 1, 2 Hypogonadism affects 5

Efficacy Parameter Saxagliptin 5 mg Insulin Metformin N 304 Placebo Insulin Metformin N 151 Hemoglobin A1C N 300 N 149 Baseline mean 8 buy cialis online